“I was no fucking prodigy!”

This surprising declaration was seethed by pianist Ruth Slenczynska in response to the innocent query, “What was it like to be a child prodigy?” This incident was more than 30 years ago at a master class in Detroit. Slenczynska added, “Anyone could play like that if they practiced 8 hours a day.”

Slenczynska was wrong. By all accounts she was a world famous “prodigy” by age 7 and few could ever “play like that” at any age. The seething profanity was her reaction to an abusive father, who forced her to practice and was physically and emotionally abusive as recounted in her painful book, Forbidden Childhood.

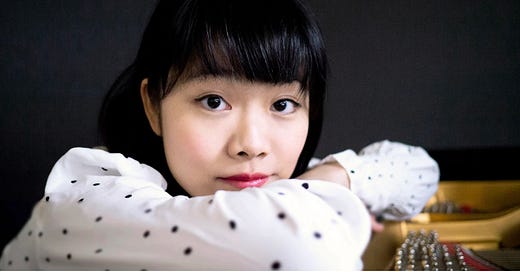

By contrast, my friend Tiffany Poon was also a child prodigy, the youngest pianist ever admitted to Juilliard’s pre-college program - at age 9. She simultaneously enrolled at the Calhoun School where I served as head until 2017. She graduated, attended Columbia on a full scholarship, majored in philosophy, and is now forging a remarkable career as a rather new kind of classical artist.

Unlike the seething Slenczynska, I first encountered Tiffany practicing Mozart on the school’s new Steinway during her lunch period. Her playing was - is - exquisite. Also unlike Slenczynska, Tiffany’s parents are not musicians and were as surprised as anyone might be when Tiffany began picking out tunes on a toy piano at age 3.

These women represent the bookend experiences of talent.

The notion of “talent”is complex, rather like the SCOTUS Justice Potter Stewart’s quip about pornography - “I know it when I see (or hear) it.” Semantics aside, there inarguably are humans, including children, who are unusually able in ways that most are not. These attributes (I avoid the word “gifts” as assiduously as I avoid “gifted.”) can be physical, mathematical, musical or within any of the realms loosely categorized as multiple intelligences.

At one bookend is the “tyranny of talent,” a wounding that is seldom as extreme as Slenczynska’s childhood, but is an insidious affliction of millions of children. This affliction can be roughly stated as the expectation that a child must do something because they happen to be very good at it or appear to have the potential to excel. How many tall women and men have to fend off the bewilderment of those who cannot understand why they don’t play basketball? Or run track because they are fast? Or train for the Olympics because they can swim butterfly in elementary school?

This affliction is particularly pronounced in music, where early facility draws great pressure to “realize” one’s potential. Slenczynska’s father was a failed violinist who evidently sought to redeem his disappointment through his child. The disappointment of parents wreaks havoc on the lives of a great many children. You might know a few.

The pressure is most widespread and corrosive in the school world, where children who are particularly capable at traditional academic tasks, are gradually boiled in a pressure cooker of Advanced Placement courses, “elite” college expectations, valedictorian competitions and parents’ ambitions for their professional lives. “My son the doctor!” has not been rendered less toxic because it can now be “My daughter the doctor!” too. More than half of the students who grab the brass ring of acceptance at the most selective colleges are receiving mental health treatment. The brass ring is tarnished indeed.

The other bookend is one I’ve encountered countless times when parents - or students - contemplate the pursuit of what the culture might term impractical - often meaning “doesn’t pay well.” Should a swimmer devote years pursuing an Olympic dream instead of going to law school? Should a young woman or man chase a career in theater or dance despite the overwhelming odds against noteworthy success? When the chances of making a living as a poet are near zero, should the quest be encouraged?

In every case my advice is “Go for it!” As every person will face inevitable disappointment, compromise and reconciliation, the opportunity to chase a passion with passion is among the purest human inclinations. Furthermore, the chase itself is rich with learning and satisfaction, no matter the final destination. And, as I often added, “You can always become an accountant later on.” (No insult intended. Accounting may be in someone’s dreams.)

Tiffany Poon is one who may fairly be characterized as “born to do it.” Her intuitive musicality as a child was otherworldly. That she chose it herself makes it deeply satisfying to watch her success.

The good news about Ruth Slenczynska is that she finally recaptured music on her own terms. Now 98, she recently recorded a new album and seems to be irrepressibly cheerful.

Would that she could have gotten to that place without the anguish.

How I miss your easy upbeat energy and take on life ...!

ANY time you find yourself in NYC, let's play!!

xx!!

Steve Nelson your writing always hits direct to the bone ...loved your passion in the "go for it" exclamation ...and the reminder that "the chase itself is rich with learning and satisfaction, no matter the final destination." I often think of the book "Moby Dick" where the chase for the unattainable great white whale makes for the great adventure :) Thanks for your always positive light xx Lisa Heffter