Damned if You Do - Or Don't

In this week’s New York Times Magazine, Yale Law Professor Stephen Carter makes an interesting, if not convincing, case for nearly unfettered free speech on college campuses. His main notion is that colleges and universities should be, first and foremost, places to encourage and exercise curiosity. Curiosity, he argues, should open minds to opposing or conflicting points of view, leading to dialogue and reflection, not polarization and censorship. In such an environment, he claims, much of today’s campus turbulence would be moot - or at least muted.

In a separate Times article, Barnard College’s new policies about speech and activism aroused a spirited debate among readers, demonstrating that education leaders are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. The Barnard case, in brief, is about the College’s right to control public information, including the right to remove political material from departments’ websites and other locations. The operative theory is that the College has the right to control what is or is not expressed using its resources or on its physical or virtual walls. Barnard officials maintain that faculty members and students are free to express personal positions, however objectionable to some, on their own, but not on the College’s dime.

There is great deal to unbundle in these overlapping issues. First to Barnard.

Despite the cacophonous nature of arguments about speech rights, especially on campuses, I’m reluctantly with Barnard on this one. I write “reluctantly” because there can be all manner of hidden agenda and cowardice associated with administrators asserting controlling rights. Nonetheless, as a former head of a private school, I can imagine utter chaos ensuing if faculty members and students felt empowered to use school resources to amplify their messages, no matter how I might agree or disagree with the viewpoints.

It can be painful. One such case, albeit slightly different in some respects, arose when a talented, idealistic student auditioned to be the musical performer at his graduation. His rap/hiphop chops were professional, and the song he proposed was a powerful anti-racist piece with tough lyrics. The College Counselor vetoed the performance. The student appealed to me, well aware of my anti-racist bona fides and my strong progressive, student-centered philosophy. He was sure I’d reverse the decision. I did not.

I told him that graduation was not his platform and that freedom of expression was not a relevant argument. The commencement ceremony was for all students and their families, many of whom would be - might be - uncomfortable or offended. I told him that I love discomfort and don’t shy away from offense, but . . .

He was unconvinced, angry, and disappointed as was his father, who stopped by my office to make another unsuccessful appeal. They are probably still mad.

I said we could do an Upper School assembly, challenge everyone, and discuss it before and after. I also said he was free to set up on any public corner, including outside the graduation theater, and say, sing or play anything he wished. I added that I hoped he had better judgment, but that such was his unquestioned right.

Which is a good reverse segue to Stephen Carter’s piece.

While I enthusiastically agree with Carter’s assertion that higher education should be about curiosity and the intellectual growth it stimulates, he is a bit late to the party. The curiosity and open-minded, open-hearted debate train left the station long ago. The tracks leaving the station were laid over the years by really lousy public policy and practice.

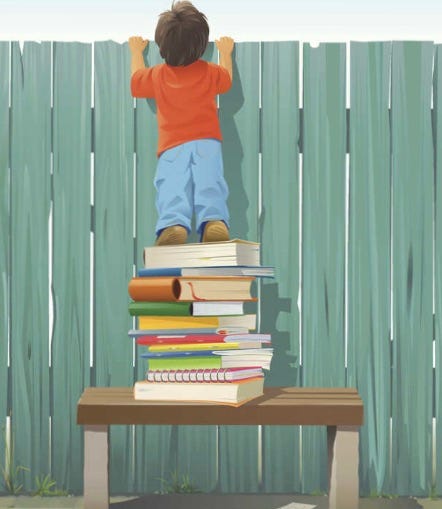

A great deal of my book, First Do No Harm: Progressive Education in a Time of Existential Risk, deals with the abundant evidence showing that direct instruction, testing, stress, and competition steadily diminish curiosity in children after 3rd grade. By 8th or 9th grade, curiosity is essentially gone. Thereafter, even if some curiosity survived, secondary schools and their practices further deflate it. Classes are too large for meaningful discussion and debate and intellectual risk-taking is dangerous to the GPA and college admission. Standardized tests, up to and including the SATs and other College Board crimes, condition students to believe that there are right answers and wrong answers - not complex and confusing possibilities incorporating many viewpoints. Ask most college professors, especially at so-called “elite” schools, and they will acknowledge the high percentage of students who only wish to extract the “right”answers in order to reiterate them on the next high-stakes exam.

I propose that this at least partially accounts for the stridency and inflexibility of faculty and student “activism” in immensely complex matters like the Israel/Gaza/Palestinian quagmire. Here, various positions have facets of merit, but proponents are more insistent on being right than in being curious. This insistence is reinforced by viewpoint conformity on cable channels and by social constructions that encourage grouping by pre-existing experiences and biases.

I know that many educators subscribe to this blog. I’d love for you to offer your own experiences and viewpoints.

I’m curious.

Steve, I was struck by this: "I told him that graduation was not his platform and that freedom of expression was not a relevant argument. The commencement ceremony was for all students and their families, many of whom would be - might be - uncomfortable or offended." I agree with your decision but immediately thought of Colin Kaepernick and the NFL's "dime." I have long supported the taking of the knee, the raising of the fist, but when I read and agreed with your decision, I felt the discomfort of what may well be my hypocrisy. Is there a difference between offensive political lyrics and offensive political gestures if they are both considered speech? You succeeded in making me curious about my own stance. (I certainly couldn't agree with you more about the bludgeoning of curiosity in our schools--including most of those that call themselves progressive--and, I would add, our colleges.)

This whole debate has come up in the context of pro-Palestinian rallies on campuses, which universities have tried to shut down because, as you say, it's "political". Yet none of those universities have shut down any pro-Israel rallies. So the message is opposing genocide is "political" but supporting it is just the American way, I guess.